A Solo Hike in the Pickets

by Ancil Nance

It was a hiker's worst nightmare. Five feet below me was the ground, somewhere above was the sky, and all around were snow-bowed mountain ash, vine maple, salmonberry bushes, and cedar saplings twined in what always looked like an impenetrable mat. Each step was tenuous, on springy vine maples bent over from the winter snows or on the ash, five to eight inches in diameter, but growing horizontally for half their twenty-foot length. I was counting feet-per-hour for progress in some sections. Sweat cascaded off me like I was taking a shower. I could hear the tumbling of Goodell Creek maybe 100 feet away. A half hour later, scratched by the thorny salmonberry and devil's club vines, I reached the creek's coolness and waded in, scooping up water by the face full. Had I made the right decision, was it too late to go back? Back to the headwaters of Goodell Creek where I had left the unmarked cross-country track called the Picket Traverse?

Up to that point I was having a pretty good time:

all alone in the wilderness, camping out on mountain passes with unending views, traversing glaciers, ridges, talus slopes and cliffs in what is one of the most isolated parts of the North Cascades. I had begun my trek at Hannegan Pass. From there a trail led to the Chilliwack River, across to Easy Ridge, and after more than two hours of climbing a crooked trail I was at a beautiful campsite, Easy Ridge, with its tarns and unrelenting beauty.

There I spent my second night, resting and thinking about the route ahead.

Halfway along Easy Ridge the trail disappears and the route angles down toward a chasm called Perfect Impasse. When I was here in 1974 a snow plug gave us passage, but now it was a bare rocky chute and I opted to descend around its difficulties, even though that meant a descent of 800 feet,

and the additional climb up to Perfect Pass.

Perfect Pass, had someone been too poetic with that name? No, this really was perfect: abundant campsites, glacier-fed streams, sunrise and sunset views, and easy access to Mt. Challenger and Whatcom Peak.

SEVENTEEN YEARS LATER, A SOBERING SOLO SHOT

Years ago, in 1974, I had been here with five friends, looking out across the Challenger Glacier, the first leg of the Picket Traverse. We

had heard it was a difficult cross-country trek. Nine days and 35 miles later we all agreed. It had been a real adventure. Now I was here again, hoping to recapture that adventure, and, to add a bit of difficulty, I was going to go solo.

Anticipating yawning crevasses and collapsing snow bridges I had half dreaded the solo glacier crossing. The day before I had climbed the rock ridge as far as possible to see if I could avoid the glacier. On the way up I came across a brass plaque on a stone, commemorating a helicopter crew that had crashed while on a rescue mission. It was a sobering reminder. I was on my own. No rescue possible, until perhaps long after it was necessary.

I rose early and headed out over the hard snow. The glacier proved a snap to cross, and I was soon descending the second notch west of the summit.

I had planned this trip as a five-day adventure with enough food for ten days. One reason I thought it would take less time than before was because I was going solo, so there would be no roped climbing or rappels to deal with. Another was I figured I knew the route and would need less time to get past the few tricky sections, one of which lay just ahead, below Crooked Thumb.

I had remembered a long ledge leading down to a snow field, after descending a moraine ridge. It wasn't there. Forty-five minutes later I discovered I had descended too far, and the ledge was only a minor part of the maze that led down to the snow. So much for saving time because of my good memory. Crossing a high-angle talus of 18-inch boulders I no sooner reminded myself to go slow, this stuff could break a leg, when my right foot flung itself downhill, costing me my balance and sending me crashing to the ground where my left knee slammed against a very hard rock. "Ouch, and oh no!," I thought, this could be the end of a very short adventure. But my knee held until I reached a snow patch where I buried it for a frosty 15 minutes. It was a warning! I could still walk, but my left knee only felt good in the snow. I wasn't halfway yet, and could turn back, but a mile of traversing brought me to Picket-Goodell Pass, another incomparable view. I slept with a snow pack on my knee, and in the morning found I could continue.

Previously, at Picket-Goodell Pass, we had holed up in our tents for two days while it rained, and on the third morning we found a way down the cliff in thick fog. This morning, despite a weak knee, I was confident of a quick descent. An hour later, in bright sunshine, I still couldn't find the route. Instead, I took the Becky alternate, higher up the ridge, and it wasn't until I was below the pass that I was able to see where we had descended in the fog years ago. Goat trails led down the steep cliffs to the beginnings of Goodell Creek. I looked across to the steep, 2,000-foot climb out of this valley. So far the trip had been what I expected, except for finding the way less than obvious. I had a compass, the Hikers Map of the North Cascades, copied pages of the Becky guide and the Tabor and Crowder guide, and an altimeter. It was easy to tell where I was, and where I had to go. I had been over this before. I had not, however, followed Goodell Creek from its source to the Skagit River at Newhalem. Maybe no one had. Newhalem was where I hoped to end up—the terminus of the Picket Traverse. I could try a new route and get there a day sooner, or so I thought, and my knee rejoiced.

HOPING HOPPING GOODELL CREEK WAS A GOOD CHOICE

Against my better judgment I began boulder hopping Goodell Creek away from the ascent to Picket-Goodell Pass. After a half mile of making good boulder-hopping time I congratulated myself on a wise decision. Shortly, however, the creek presented an obstacle: a large collection of boulders too big to hop, in the stream bed. A detour through the underbrush was necessary.

There was underbrush and overbrush and on-top-of-me brush. It should have been a warning: Go Back! Once, I did look back toward Picket-Goodell Pass, now 2,500 feet above me. That was where my route should have gone. I had showed the park rangers my traverse route, and they said if I wasn't out in ten days they would begin a search. Now I realized that a search would reveal nothing of me because I wasn't where they were going to look, which meant that I had to be sure I made it out in time.

It was one thing to be stumbling along a rocky traverse in plain sight. It was going to be quite another if I got injured in this green Hades. That gave me something to think about, but I continued anyway. After all, what could happen? Plenty, I soon learned. After more boulder hopping, the creek went merrily downward toward a narrows where it lost all control and plunged and careened through steep gaps and falls. So it was back to the undergrowth for me, and lunch time was already upon me. I fought through more tangle, and now there were huckleberry bushes mixed with the other barriers, so I scarfed them by the handsful. I then noticed that I was on somewhat of a trail, or at least the going was easier for some reason.

The thought occurred to me that it was a game trail, and perhaps I was the game. The way forward would have been more obvious if I could crawl on my hands and knees like a bear, I mused. What a great place to be a bear. To the right I noticed large house-sized boulders, and then I smelled something animal-like. What I was slow to admit was that I was in bear country. I hoped there were enough berries for all of us as I began making my way noisily forward, clanging my ice ax on the rocks and speaking loudly to the green tangle.

At last, back to the stream, I was able to jump to a small island and rest. I wasn't the first to make that jump. There on the ground was a pile of droppings that were like logs: three inches thick, 15 inches long. Cutting my rest short I hoped I wouldn't meet the mouth that helped create those droppings. A grizzly bear perhaps? That first day on Goodell Creek I climbed over more boulders, crawled along more bear trails, fought more green tangles. Each step over boulders or along logs over rushing current, or in the green tangle now became more deliberate. I realized that one close encounter with a bear could put me in danger, but even more likely, one slip off a log into the creek (by now a tumbling torrent) would mean no one would ever find me.

I imagined someone coming down this way ten years from now and finding, there in the brush, a skeleton, an orange pack, some loose fitting clothes (mostly rotted off), and an ice ax imbedded in the skull of an obviously large bear, weathered white but still dangerous looking. That image made me slow down. I couldn't afford to get tired out, slip, make a mistake. This was more dangerous than I had thought because every step could be my last. By now the creek looked like something coming out of the Himalayas. The bypass through the forest and green hell sometimes lasted for an hour and I would progress 300 feet downstream, with elevation drops close to 150 feet. There were times when I could see no way onward, and standing there I had to tell myself, "you can either look at it or do it, but if you look at it long enough you won't get home." This would calm me enough to put up with the slow picking, scooting, slipping, jumping, sliding, and climbing that faced me whenever I had to leave the creek. My perspective was changing.

DANCING WITH DANGER CREATES ADVENTURE

An adventure is anything with danger as a partner. Shopping is an adventure if you're in danger of going broke. Outdoor magazines are full of adventure accounts in exotic places where ordinary mortals will never tread. But here I was with a real pocket-sized adventure ten miles from a tourist-clogged road. I had turned a quick hike across some ridges and valleys into a lonely plunge beyond help where every decision and step had a consequence that I would have to live with until I got out to the trails again.

This was just as good as being 1,000 miles from help. I was beginning to think, rolling ideas and scenarios around in my head like someone taking a really slow bite of chocolate mousse; If I slipped into the stream I could hit my head and drown; If a big bear wanted me for a snack I couldn't stop him; If I stepped off a boulder or log into a deep hole I could sprain my ankle, or really ruin my knee, which could cause me to take longer than ten days for the trip and the Park Service would send searchers in the wrong direction. And so on. I was enjoying it because as the danger increased in my mind the adrenaline rushed out to the imagined excitement.

Now I was really having fun as I tore at straggly branches, ducked and plucked at thorns, and guessed ahead what route would be best over the boulders, down the cliffs, and across the creek. "Slow down, you're going too fast," from Simon and Garfunkel, hummed my brain. Speed is a point of view and by the end of the first day in the creek valley I had made three miles in ten hours. I'm used to something better than that, but from the perspective of a small biped in a dense forest it was fast enough.

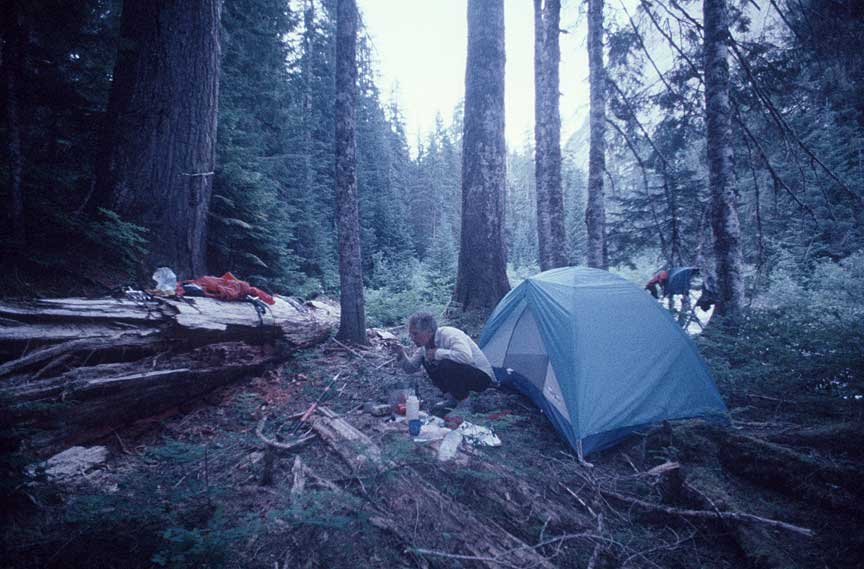

A clearing in the old growth was home for the night. I still felt like a mildly tolerated guest and I hoped a bear or two wouldn't come

poking around. Just in case, however, I did rope my food bag high over a limb. My previous camps had been on high passes with lung-grabbing views. Tonight, five-foot diameter cedars and firs watched me instead. If darkness "falls" anywhere it is here in the forest. No stars, just dark, with little noises. Soon, all that was gone in sleep and by dawn I was ready for another struggle over the rocks and through the brush. Goodell Creek was as relentless in its steep twists and turns as the undergrowth was thick. I would go a ways through the forest until I figured I was past the obstacle and then slide, swing, and cling down steep slopes through stickerbushes for a short walk along a flat portion of stream bed covered with small cobbles.

The cold water was good for my knee, it hardly hurt. It was another hot day, and lunch break included a short swim in a pool

beneath a water-covered boulder. After lunch a long easy stretch in the river bottom made me hope that I would make it to the trail before dark. Several detours around steep 100-foot drops over boulders as large as chicken sheds eventually slowed me enough that I got to spend another night camped on the river edge. It was still called Goodell Creek, but it was more like a small river. The map showed an island about a mile from where the trail came close to Goodell Creek. I camped there on the sand, ate two freeze-dried meals and crawled into my tent, knowing that I had made it.

The next day was easy boulder-hopping and brush pushing for a couple of hours to the trail. The trail! It was like a superhighway compared to what I had been through. I have great respect now for any of the old-timers who made first ascents and descents in any forest or jungle land. Maybe what seemed so impossible to me they just took for granted. I don't know. I saw when I got up close to each problem that there was a way, nothing was impossible without a way around it. One step at a time. Just like the rest of my life.