Is there a place or time that was so good that you sometimes long to return there?

Chapter 1

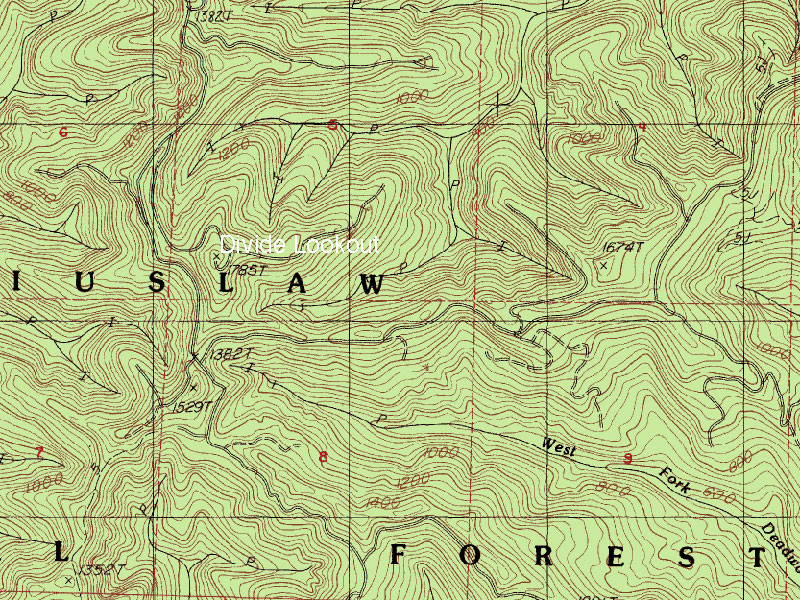

I could not concentrate on my work, a restless tugging got me thinking about driving 150 miles to the location of my former fire lookout tower. I knew it was gone, torn down years ago. I knew that the 1785' high hill, called Divide, was overgrown with trees and I would not be able to see the surrounding landmarks. I had visited Divide in 1972, eleven years after my last summer there as a U.S. Forest Service fire lookout. In those few years new growth trees were already 15 or 20 feet tall, and thick enough to block the views. So why was I going back again?

I spent three summers on the Mapleton Ranger District, the first summer working on the trail and slash burning crew. The next two I worked as a fire lookout on Divide. I was fresh out of high school, and this was my first real job, working with older men, taking orders, being responsible. Before going to the tower and during my first year at the ranger station, I lived in a bunkhouse with other trail crew and lookout men. We each had a space that consisted of a cot and a closet. Then there was a shared space, the bathroom, the kitchen, the hall. Each man took a bit of his own space with him when moving about the bunkhouse. Leaving a mess behind was not tolerated, so the place kept reasonably clean. Considering that each day we would return sweat soaked, dirt covered, and sometimes smoke filled, dirty short-cuffed jeans hanging above our "corks," it was a wonder that the weekly sweeping and toilet swabbing was all that was necessary.

Even though I had my own car I did not think that I needed it that first summer, so my mom and dad drove me there. I was a bit embarrassed, getting out of the car and saying good bye to them with a few of the other men standing around, eyeing the new kid. I was on my own for the next three months and full of anticipation. Right off I met a kid my age named Walt Koch, and anxiety withdrew. The bunk house was his new home too, even though he was from the area, Mapleton. He was a burly guy and he challenged me to an arm wrestling contest. I held my own, and through the summer we proved to be about equal.

There were three or four other guys there too. One was on trail crew with Walt and me. Another was an engineer for the road crew, and one worked as a surveyor, running P-lines for future roads. Sometimes, when trail crew work backed off, I was able to score the cushy assignment of going with him, Johnny Calvert was his name, to hold the sticks he sighted on for the correct route. Those days would start with a stop for morning coffee at a cafe. The first time we did this I had not been a coffee drinker, but the waitress, on seeing how many of us were coming through the door, already had cups poured. I just played along, thinking, "Not bad." We drove many miles back to the end of some road and started walking and plotting the continuation, sometimes miles into the forest. This was easier than digging trails or burning slash, and I only drew that assignment a few times. Johnny had a wry sense of humor, and also a '53 Buick. At the end of 5 weeks I had some time off and he gave me a ride back to Portland. I picked up my own car, a '41 Chevy coupe, for the return trip, since now I knew that some weekends would be free. Overtime was plentiful during fire season for anyone who wanted it, so I did not go back home every weekend.

Fourth of July weekend, 1959, was one that I stayed to work overtime. I was asked if I wanted to drive a pumper rig around to several recently burned clear cuts, and I would get paid time and a half. Saying yes was easy. This was just the kind of work I liked, and I was glad for the responsibility and secretly proud to be so trusted. I had apparently proven myself. The weather was hot and dry, so there was a chance for a flare-up of the burns. In fact I did find three hot spots that had begun to smoke. One, near the bottom of a ravine, required me to run 1,000 feet of hose. I doused the smoking stump with as much water as I had, stirred the ashes with the shovel and checked it with my hand. I waited long enough to eat a sandwich and left to refill the water tank. From then on I was given more assignments that let me be on my own, but I recall that one as really building my confidence.

Another confidence builder was the time that the assistant ranger, Phil Edgerton (I think) and I had to take driptorches filled with diesel mix and set fire to areas in a burn that had been skipped by the main blaze. We started off at the top and zigzagged down the 100 acre cut, torching slash, climbing over slash, crawling under half-burned logs, and the ambient air temperature was over 100 degrees. The flames and smoke made it like an inferno by the time we reached the bottom. I could see that Phil was tired but trying not to show it. I did the same. At the bottom of the cut we came upon some water embedded in slow moving mud. I placed my shirt down on the muddy water and slurped, but still got more dirt than water. We made it back to the truck on what I deemed to have been the hardest day of work I had ever had. I had kept up with the pro, had not slipped or twisted my ankle, and again had proved myself. This first summer was packed with other such incidents, each one showing me a bit of myself.

I watched others grow also. Our trail crew set out one morning to build a trail around a recently logged clear cut. It was several miles into the Coast Range above the North Fork drainage. We stopped near the clear cut on a bit of a slope, and piled out. While we were getting organized someone yelled "The Jeep!" Looking up, we all saw our rig, a 4WD Willys Jeep carryall, moving backwards down the road toward a drop off. The foreman, Manuel, streaked to the Jeep and lunged, his torso disappearing through the open driver's side window as it picked up speed. His legs hung out, flailing. It seemed as though he was going over the bank with the Jeep. Just in time he pulled the handbrake. The Jeep, his job and his life were saved. No one spoke. We all knew that not a word would ever be said about what happened. I listened and understood.

The rest of the day was uneventful. My part in the trail building was to wield a Pulaski. This is a double headed tool, an ax and a mattock and probably the best tool for trail building. A couple of guys with a chainsaw prepared the way for us, and others with axes chopped smaller brush, but it was the Pulaski swingers that got the trail down to dirt. We were classed as Laborer III on the pay scale, and I am not sure how much that was per hour. A couple of bucks. But we were treated fairly, getting breaks before and after lunch. During my breaks I would usually reach for a pack of carrot sticks, while the others smoked. I learned then that it is not good to work too much faster or more than the rest of the crew. They resented the increased pace and there seemed to be an understanding about what that should be.

About half of our crew lived in the area and were picked up on the way to the job sites. One man, particularly mean, would always sit next to a kid from the area, Jim, and pinch him often enough to be a real bother. I could never figure out why he enjoyed pinching the kid, who was probably not out of high school, but he was big enough to do the work. His tormenter was smaller but wiry, about 35 or 40 years old and spoke with a drawl. Neither of them seemed like college material, but that did not matter. It was the being mean just to be mean that I did not like. And if the kid moved, the meany would mange to keep near. I made sure to never sit next to either of them when riding to and from the work.

I enjoyed the work, thinking about how it was keeping me in good shape. I planned to try out for wrestling when I got to college, so I was on track. However, when I heard that the next year there would be an opening for one of the district's three lookout positions, I applied. The next summer, 1960, I started a new life.

Well, not totally new. Before we went to the towers we had to do some trail work, and we went to a lookout training school in Waldport, on the coast. The school was sort of like advanced Boy Scouts. We had a week of learning how to go across country on a compass bearing. How to put out fires, first aid, and other skills. There were three of us from our ranger district in attendance. The district only paid for one room and one bed, at a motel called Tilly the Whale. One of the men, Bob Randell, said we could all sleep in the one bed as long as no one farted under the covers. That cracked me up. It was a fun week. My new life as a forest service fire lookout had begun.

Chapter 2

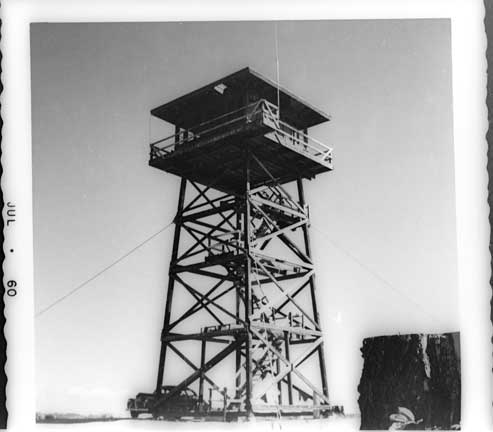

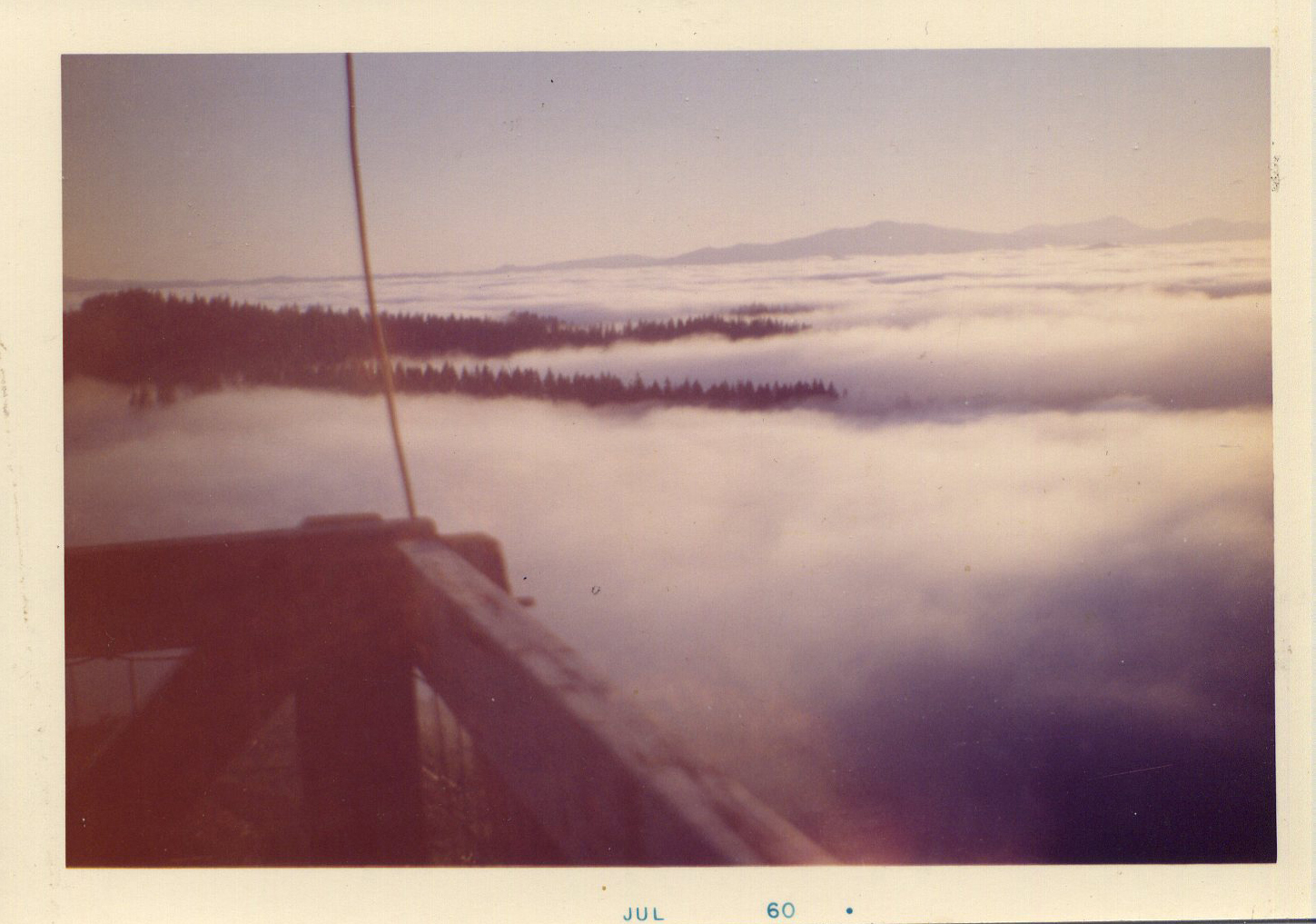

My lookout was called Divide because it sat in the middle of the coast range at the head of drainage systems that went north and south, east and west. It was not very high, as lookout mountains go, only 1785'. The tower itself was 40', so that put me over 1800 feet above sea level. I was half way between two east west highways, 34 and 36 and halfway between the Willamette Valley and the Pacific Ocean. For two summers the 14'x14' box on 40' tall supports would be my home. My job was to scan the forest around me for fires, particularly after lightning storms and following slash burns. Sometimes sparks would travel downwind. To do this I had to know the territory around me so that I could give the correct location with the aid of the azimuth rangefinder that dominated the center of the room. Fire and weather reports were transmitted by radio, and my call sign was Oboe 22. Every morning I would go down to the weather station and take two temperatures, the dry and wet, and relay that info back to fire control so they would know the dew point for the day.

I had a backpack water pumper, but only used it once to get a small smoke in a recent slash burn about a mile from the tower. That was unusual, since my main job was to keep and eye out for fires, not fight them. One morning I awoke and in the new light I could see a tall smoke to the north. Turns out that the school at Fisher had burned during the night. It was about 10 miles away. The lookouts along the coast did not have a lot of action from lighting storms, compared to those in the Cascades or further east. Mostly our job was to keep a flow of communication for crews in the forest and to watch downwind from the controlled burns. The evenings were not part of our on time unless there was a lightning storm so sometimes I explored the outer roads, just to get to know the country.

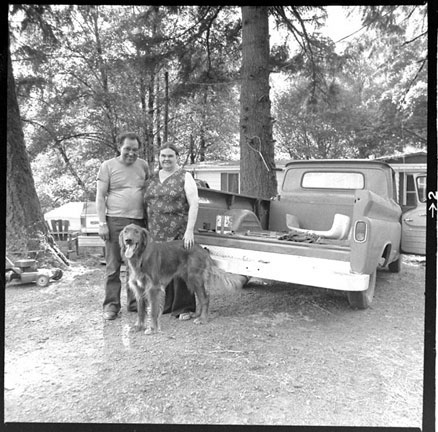

One time my car got stuck in deep fresh gravel on a new road, a couple of miles from the tower. That night I walked back to Divide. In the morning I returned on foot to meet the road crew. They used a road grader to pull my car free. I had some explaining to do, but I was forgiven since it was all in the interest of knowing my territory. About five miles north of Divide was the place called Paris, at the time there was a sign so saying. Now the sign is gone. Paris consisted of a lumber mill and a few homes tucked here and there along the gravel road. When I visited in 1981 the mill was being dismantled by a couple, last name of Philips. When I drove by Paris in 2007, the Philips were gone and the mill was just a collapsed hulk, machinery all removed. I had a visitor from Paris that first season on the tower. His name was Buzz Martin*. He could sing and play the guitar, sounding just like Johnny Cash. He had a band called the "Five Rivers Three." He invited me down to his place and I went a couple of times each summer to hear him play and sing; a great way to end the day and a nice change from the usual book reading by Coleman lantern light.

My day was pretty much my own after the weather report. Yes, I had to look carefully on my check-look time, and sort-of carefully the rest of the time. I had a pair of binoculars that were required for the check-looks, which were staggered 20 minute sessions with the other area towers. This left plenty of time to read, get a tan, target practice with my slingshot and pretty much dream of things to come. On cloudy days there were chores away from the tower, sometimes joining a trail crew, or painting the tower house and the outhouse. Dick Long, the assistant ranger, gave me a couple of cans of white paint for the interior of the outhouse. I had some left over so I painted the recently exposed stumps that surrounded the tower. Divide hill had been logged, so I was in the middle of a small clear cut knob. At night I could see the glow of the white topped stumps. Dick came to check up on me a couple of weeks later and could not figure out what to do with me about using good paint for stump tops. He just smiled and left. On this return trip I found one of the stumps had survived the tower destruction and the recent logging. I could not believe my eyes.

I reached to touch the rotting stump and a chunk came off. I looked closely and yes, paint still remained from 1961. I really had been there and really had painted the stumps. Silly of me to think that I needed confirmation, but just that moment of picking up the piece of painted stump top was a real step back in time. I stood there crying with joy. Some important events must have happened there those two summers in the '60s. What were they?

Broken-hearted Melody by Sarah Vaughn, the number 7 song in 1959 was still getting played a lot on the radio in the summer of '60. I had a small battery powered transistor radio, itself a fairly new gadget in 1959. I would tune to the Eugene stations and get pop and western songs all day, along with a weather report given by a woman with the sexiest voice allowable on the airwaves. She reported the temperature and the heat went up everywhere. I was a bit broken-hearted, because I was away from my girlfriend. We had been good friends for over a year and it was tough being apart. My mom and sister surprised me with a visit, and Marilou came with them. They only stayed a couple of hours but I long remembered our time together. By the summer of 1961 Marilou and I were maybe not as close or maybe she was getting ready to go to Japan as an exchange student. Something was not the same. Standing there holding the piece of stump I wished that I could recall the second summer better. By the summer of 1962 I had another lookout tower, on Sisi Butte in the Cascades, and I was writing to a new girlfriend too. It is the lost memory of 1961 that haunts me.

I do recall some incidents, however. I was thinking about staying in good physical condition, despite the life of ease as a lookout. One day I put on my boots and the plan was to run a mile and see how I felt. I ran down the tower access road about a quarter mile and stopped. I had done something to my legs, they were in great pain and I barely made the walk back to the tower. For the next couple of days I had to move slowly. I had stretched my tendons by over-reaching my stride downhill with heavy boots. I gave up running. I eyed my arms, which had not been worked nearly as hard as the summer before when I was on trail crew. I decided climbing the tower guy-cables would be good exercise. The cables holding the four corners of the tower platform were about an inch and a quarter thick. I was able to climb the cable, hand over hand 40 feet upwards and exit at the top near the platform. One time a visitor and his daughter happened upon me in mid climb. He asked if I could do it again, but I declined. Once a day was about enough. Another time a visitor arrived in the morning. I had not shaved yet but was preparing to. I saw his car a quarter mile down the road so I tore my T-shirt and wiped shaving foam around my mouth. When he got out of his car I went out on the catwalk screaming and ranting, as though I had gone nuts being alone. At first he looked shocked, but when I started laughing he saw the joke.

It was no joke when I discovered that some critter had almost gnawed through the water hose on the backpack pumper. I had no traps, but I did have a slingshot, so I kept watch one evening. Sure enough, out came a chipmunk heading right to the rubber hose. I loaded a marble, intending to only scare it away. Instead, I blasted it right in the head. I went down, feeling terrible, but I got over it soon enough. After all, I needed the hose in good condition. Another time I almost blasted my foot, with a borrowed 22 pistol. A friend loaned it to me for a month and I had been shooting at targets on stumps. It was a nine shot High Standard. After a session I walked back up the steps and part way up I pulled the trigger, thinking it was out of shots. BAM. Right in front of my big toe, on the stair tread was a small hole. Lucky me, I thought, feeling like an idiot but glad that I didn't have to explain that kind of accident to my boss.

Life on the tower was a paradox. Confined to total freedom. I read books and listened to the radio. I had a Brownie Hawkeye camera to photograph the sunrise and sunset and the galloping horses that I saw in the rising vapor clouds on days when the sun arrived to round them up after a wet night. I don't think I could have sustained the life much longer than the three months of the season, and I took advantage of every day off by motoring to Portland to go on a date and hang out at my girl friend's home. She had great parents, her mom was always a mom to everyone. Her dad was a geologist for the state, and he knew things that I wanted to know. I took geology as one of my science credits and was captured by the many ways to categorize the earth. I learned that my tower rested on Tyee formation sandstone. Somehow that meant more to me because my girlfriend's dad was a geologist. I could see my knowledge reaching out and connecting with people in new ways.

Despite having radios, we lookouts could not chat on them. So when I wanted to connect to one of the other lookouts I wrote letters, and they returned their thoughts in similar fashion. Patricia Veronica Lake had the Roman Nose lookout. She was a Catholic. Ray Spaulding, a Jehovah's Witness, was over on Herman Peak. And Walt Koch, even though he was not a lookout, took part in the letter discussions. He brought a Seventh Day Adventist perspective. I was the Baptist kid. Yikes! Looking back I think now that I did not know how formative were our letter discussions.

Throughout the summer we wrote back and forth discussing various aspects of our Biblical beliefs. I wondered why Catholics put so much trust in the Pope, why it mattered what day Seventh Day Adventists went to church, and how the JWs could be sure there were going to be 144,000 saved at the end of the world. I can't remember now what some of the more meaty questions were, but I do recall thinking that it was strange for all of us to be looking at the same book but coming up with such different results. I was still certain that I was right. Ray, the Jehovah's Witness, said he too was certain he was right. "Why believe something unless you think it is right?" he asked.

That was the beginning of a rational journey for me. It took a while. I went through four years of college still as a Baptist kid. A history course, U.S. in the Twentieth Century, taught by James Hitchman, was a highlight of those years. After one class I felt that I finally knew what history was. Not sure if I could now say what that was. The course was a continuation of the mind opening that had begun on the lookout tower. There was a text to read and a paper to write, but the best part was the discussion session. Hitchman gave us a list of books to choose from. The books were not history books. Instead, they were taken from philosophy, sociology and religion in the twentieth century. I got carried away reading books by Albert Camus and Reinhold Niebuhr. Each person would lead discussions about the books they had read and I went for Camus, particularly The Plague, and The Fall.

In The Plague, the various characters react differently to the sickeness and death surrounding them, some believing in their God as both the cause of and the salvation from the plague. Others looked for natural causes and solutions. This helped me see the difference between believers and thinkers. In The Fall, the protagonist, Clamence, while walking over a bridge, hears a man in trouble. He pauses, wondering what to do. By the time he makes up his mind it is too late. He recognizes that it will always be too late. For some reason that got to me. Why would it always be too late? And was that a belief or a recognition of truth? Camus brought questions to attack certainty. Certainty fell as questions mounted. The journey begun on the lookout tower had continued, I shed some of my baggage.

I am well beyond the scope of the original story, about Divide Lookout. Perhaps it is clearer now why I return to Divide, with its beginnings of self-reliance, love and skepticism.

Location of Divide Lookout

*In 1968 Buzz cut a couple of records with the encouragement of Cash himself and appeared on the Johnny Cash show in 1972. According to a note on the CD Baby Web site, Buzz drowned in Alaska in 1983. His son Steve has re-released his songs.