Yangtze River Expedition, 1986, An Adventure

A book (8.5 x 11) with 120 full color images is available in softcover as digital one-up printing from Lulu.

Place your order with Ancil Nance or buy from Wallace Books in Portland Price is $40.00.00 w/free shipping

This is an account of the 1986 Sino-USA Upper Yangtze River Expedition led by Ken and Jan Warren. The expedition covered roughly 1100 miles from the source in Tibet at 17,600' to take-out just above Batang in western China.

We would be in China for almost two months.

Note: This is an accurate account of the descent in 1986. Other accounts exist, but they are based upon information given by members of the team who quit less than 700 miles into the 1100 mile trip. There was no "mutiny" despite the sensational headline in an Outside magazine article. Some team members quit and the expedition carried on; hardly the definition of a mutiny. The book, Riding the Dragon's Back, is based on erroneous information from the quitters. Comments by Simon Winchester in his book, The River at the Center of the World, are based, he admits, upon the anonymous interviews with the quitters. Neither Winchester nor Bangs has spoken with me to get a point of view not tainted by the shame of the team members who quit. They made disparaging comments about Ken Warren and denigrated his leadership and personalty. I think they had to do that to justify their quitting. As a team member who stayed with the Warren Expedition for the whole 1100 plus miles I can say they were wrong, there was no reason to quit when they did. For writers to concentrate upon what we did not do (the plan was to go another 500 miles) misses what we did do: continuously boated the river from the high source. No other rafters have done that. Maybe we would have been stopped at Tiger Leaping Gorge and would have had to get out of rafts and enter stunt-man capsules. Who knows? But we rafted through where others pulled out. Paul Sharpe has added comments to my original recollections and has helped fill in some gaps. His additions will be set off by an indent and grey background. Any errors that remain are mine, let me know if you see any.

Before we left Canton, in the elevator going back to our rooms after a meeting with Chinese government officials I recall Ken telling us that despite previous promises there would be no helicopter rescue so we were on our own. Later, as we were leaving basecamp I said to myself "Don't even get a cut finger, we are on our own." I did not expect a helicopter rescue at all and I do not understand why some kept thinking it was a possibility later when we were dealing with Shippee's death and further on when our rafts were damaged and the will to continue was somewhat dampened by the hugh water.

A LOOK AHEAD

Churning water crashed over our four rafts with such force that two of the oarsmen were blasted into the river, a raging torrent thrashing about like a giant brown dragon trying to rid itself of pests. Our four 18-foot long rafts, lashed together in a 36-foot by 24-foot diamond, were headed for a gigantic wave curling above us. Chu and Zhang had to get back in before we hit it. The rafts seemed to pause on the up side of the next wave, Chu and Zhang scrambled aboard as the wave tilted our craft to a nearly vertical position and then dropped it over the downstream side of a deep hole of brown and white, churning wild water.

"HANG ON," Ken roared, as the river smashed against the canyon wall and twisted into angry reversing curls and boils. Again we were hurled about like corks. I was tossed into an opening between the lashed rafts. I paused in this watery cradle as another wall of water slammed over us. I scrambled back to my place next to Ken at the left oar, only to see him get flipped off the seat, like a rag on a stick, toward the front of the raft, almost going over the bow and I grabbed him by a strap. Another wave hit, and Ken was ready, feet braced. The oar caught a powerful current, but the other end was held in an unbreakable grasp. With a loud crack the oar became Tibetan firewood. I unlashed the spare and Ken fitted it to the oarlock, ready for yet another crash of furious water. Would it ever end?

We didn't know. We didn't know if a giant waterfall was just around the corner, nor did we know if we would be able to stop before going over. That is what makes first descents different from any other type of river running. The sequence just described was just one of the many unforgettable moments on our descent of the Upper Yangtze River, the third longest river in the world and China's greatest. We will return to this part of the adventure, but first some background.

Why would anyone do a trip like this? There was a time in human history when everywhere anyone went was unexplored, dangerous territory. Those who went first made it easier for all who followed. Explorers who returned let the rest know that it could be done. Those who didn't return caused the next to be cautious, to be better prepared. Just knowing someone had climbed a mountain, run a river, or traversed a continent gave confidence to those who followed. Hearing that people had died raised caution flags.

Being the first into the unknown is missing from our lives today. It is an urge most people never get to play against. The 1986 Yangtze River Expedition gave some of us a chance to get back to our roots and push against fear with confidence and courage. Attempting a first descent of a major river gave us a chance to see how deep were our roots. When the whitewater appeared, when scouting was impossible, when stopping was out of the question, that was when I saw the essence of living. There, on the cusp of death, was the peace of existence so deep, so exciting, that it could become addictive. Mountain climbers face it. Soldiers in battle are changed by it. It is the extreme edge of life.

I got my chance to be part of the expedition when I was assigned by Sports Illustrated to photograph Ken and Jan Warren in Tualatin, Oregon, with the large mound of equipment that would supply the adventure.

After taking the photos I asked Ken if the expedition needed anyone else. He replied that he already had a photographer, David Shippee, but he did need a climber, who would be needed if the expedition became trapped in a rock-walled canyon. The next day I returned to show Ken my climbing photos and talk about my climbing skills, which I felt would be just what he needed. I also told him I was a good dishwasher. Ken agreed to take me as climber and general grunt. I did not even think of rowing a raft, as that was not a skill I had yet developed.

I had, however, been getting in shape by running trails. A few months before, on a trail in the Columbia River Gorge, I was wondering to myself why I was taking time to stay fit. I remember replying to myself that I was staying fit just in case an expedition came along that I could take part in. I was ready. I had taken kayak lessons, so I felt comfortable on and under the water. I rowed a short section of the Sandy River in a small raft, just to learn the left and right of rafting.

In just a few weeks the expedition team was on a plane for China, hoping to be on the river the first week in July. We landed in Hong Kong, then went by train and plane to Golmud, just south of the Gobi. We stayed two nights there, at 9,000', to get our bodies used to the higher elevation.

A sidewalk cobbler in Golmud prepares a shoe.

We moved all the supplies into large waterproof coolers and river bags. We were given our special clothing which included wool shirts and pants, special survival coats, wet and dry suits, knives, and thermal boots and underwear.

The road overland to Tuotuoheyen went through dry mountains and by abandoned living quarters, which may have been used as retraining centers during Mao's cultural reorganization.

Tuotuoheyen is a small post on the Yangtze along the road to Lhasa, at about 14,500'. At this elevation the oxygen content is about 2/3 of what we were used to at sea level.

The river at Tuotuoheyen is shallow and wide, with many sandbars. Down river from this crossing the river continues as a flat, braided stream for 200 more miles.

Upstream the river had its headwaters at the snout of a glacier, and was mostly a flat, shallow, braided stream. We spent a week acclimating at 14,500', and our first night there many of the team showed green gills. Despite the illness, however, there seemed to be some sort of exchange of sleeping situations going on. I never did find out what that was all about. It could have been budding romances or just trips to the loo.

Dave Shippee never did get used to the altitude and after a few days of lying sick in his tent he returned to lower elevation at Golmud while the expedition took trucks, yaks and shank's mare to the source. At first the drive to the source followed the road to Lhasa, then, after about 20 miles, the trucks left the highway, cutting west across the rolling hills between two mountain ranges.

We had to cross streams and got bogged down in axle-deep mud. The rigs were six-wheel drive army trucks, and working in tandem they were able to winch themselves through the bogs.

One truck's engine became submerged at a ford, and the driver ended up taking the head and pan off to dry the engine.

The route over the hills and through the pass had been traveled before, but it was not a road by any stretch of the word. Land expeditions had searched for and found the source.

Mt. Geledangdong in the Tangula mountains, the source of the Yangtze as marked by the Chinese explorers.

A marker had been placed on a low hill in front of the glacier to denote the source.

It snowed lightly one night on the way overland, and we met a few nomads on horses.

Halfway through that crossing we camped at a spot where we could look back from a small hill to where we knew base camp lay, perhaps 50 miles away. The river made two right angle turns in its journey from the source to base camp. So we were then in the center of the square made by the four points of the camp, the source and the river. By the end of the second day we made it to the river again. From there it was about 20 miles to the source glacier.

In order to make the approach more interesting for the film, the plan was to ascend to the source using yaks to carry gear and a couple of Tibetan ponies to give the film crew something more to work with rather than going all the way in trucks as the other teams had done.

We made camp at the river after coming through the mountain pass from the highway. It was determined that a truck trip would be made to the glacier just to check things out. The land was covered with hummocks and the truck ride was the worst part of the whole trip, jouncing and rolling ever upwards toward 17,600 feet and the pool at the source.

We returned

from the recon trip, and the next day began the two day hike, with yaks

carrying all the gear and the film crew making the source approach look

like a nice walk.

By now we were used to the elevation but breathing was still difficult, so the slow hike was just what we needed. Had we driven all the way, going from 14,500' to 17,600' in two days instead of four we may have become sick again. At the source elevation the oxygen content was a little less than half of the amount at sea level. I tried jogging, but quit right away.

Our hike followed the river as it came out of the south until we could angle directly to the source. Along the way we noted tiny flowers in hummocks and various geological features such as silt deposits and snaking moraines. A map of the area shows the river making three left hand turns so that there is a kind of spiral to get into the glacial nook where the pool forms at the base.

About two miles from the glacier the river angled west at an increased angle, but it was still not rough whitewater, just big burbles. The source was not what I had imagined before the trip: you know, a cliff with a small waterfall. Instead, it was a large glacier with a pool drained by a small stream. It would soon be our ride for almost 1000 miles.

We posed for the group photo, then unloaded the two hard shell kayaks and the 5 inflatable kayaks from off the yaks. The yak team was driven by a team of Tibetans who had the food, tents, and supplies packed to the huge beasts.

Ron Mattson is first into the source pool with a spin in his kayak.

John Glascock and Dan Dominy make a record of the preparations.

The first leg of the expedition, from the source to Tuotuoheyen, would be in the kayaks, not rafts, because the river was too shallow for loaded rafts. The yak team carried all the heavy stuff for the 8 day trip, and they would meet us at the end of each day when we set up camp.

I put my Canon F1 on the ground pointing at the sky for maybe 20 minutes or an hour on one of the clear nights when I slept outside my tent.

The weather was clear and cold for most the time and we had uneventful paddling in ideal conditions. Each morning would break with the night shadow edging away to the west as the sun crept toward us across the plateau. Once we came out of the Tanggula mountains we kept at about 14,500' most of the way to base camp.

Sunset view looking east at glowing clouds on the mountains.

From atop a stony knob I looked back toward the snow-covered Tangula peaks. Most of the river was braided and shallow, with a few swift channels.

At a point on the river about 100 miles from the source we had a camp site above which was a tooth shaped high rock from which I had a good view back our route.

The back side of the rocky tooth afforded an easy scramble to the viewpoint.

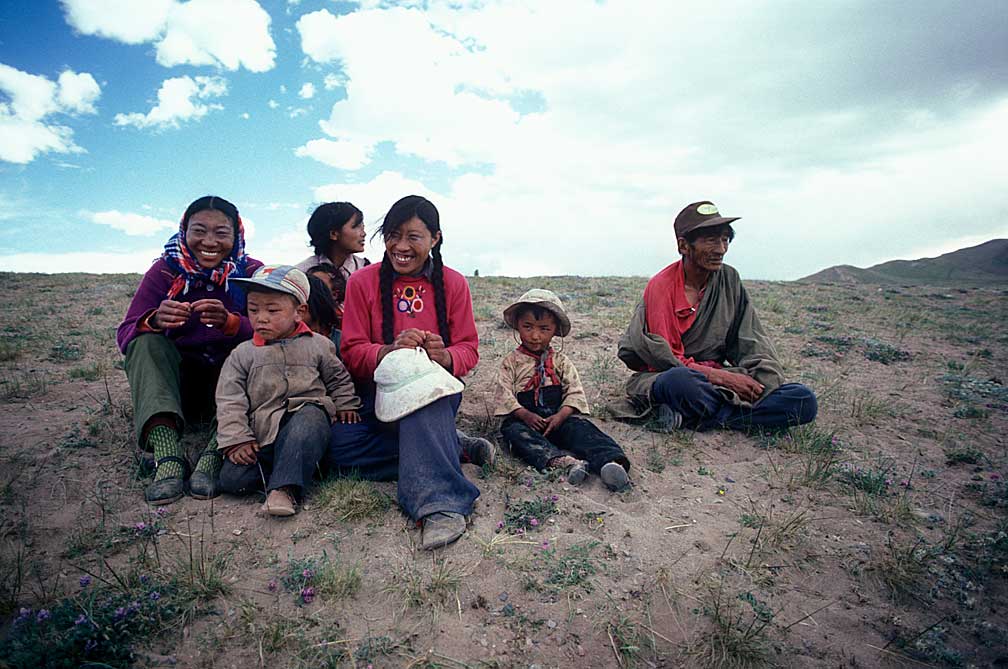

We saw nomads as we neared our destination, and landed our kayaks to have a chance to take pictures of the people, a family it seemed, reminiscent of Native American family photos.

Shortly before arriving back at base camp it was decided that the film crew should show a fine flotilla of kayaks coming ashore. This required us to haul our kayaks back up stream and regroup for a more triumphant arrival. As knackered as we were the thought of going backwards caused for some robust and derisive comments. Eventually we did regroup and the film crew was able to get good shots of the team returning to base camp after 8 days on the river. We had done about 25 miles a day and had used up all the food, so base camp looked real good to us.

Two tasks awaited us before we could begin the second leg of the river journey. One was to prep and load the rafts with the precise loads each was to carry. The second was to see who really was ready to go further. Ken had to make sure that team members realized that from here on there would be no chance of rescue and that there could be no turning back. Yushu was about 550 miles downstream and we had no idea what conditions we would encounter, though they were not expected to be drastic.

Dave Shippee had returned from Golmud, having regained his vigor at the lower altitude. He was hopping about taking pictures and helping where he was needed. Ron was getting the rowing frames strapped to the boats, Ken and Jan were dividing the supplies so that there would be food and toilet paper for the team when needed. We even had a large basket of eggs, padded with straw. Coffee and hot chocolate, canned condensed milk, flour for flat bread, peanut butter, noodles, pancake flour, the list goes on, and I am sure I could never recall all that we carried. It was amazing to me that Ken and Jan could even come close to figuring what was going to be needed. As it turned out we all had plenty of the right clothing and equipment, and we were short on food a couple of times because the travel time was longer than anticipated.

The first night out from base camp began cold and wet at "Camp Wilcox."

There were many sandbars to drag over in the first 4 days and this had not been anticipated. The river in July near the source is low, and the timing was critical. A larger flow rate may have made some upper sections easier, but downstream the conditions could have become impossible at a higher flow.

The weather was mixed, with rain and snow storms followed by sun breaks during the first four days.

A day before departure, David Shippee was sick in his tent. Some hinted that he should not go further. He told me, however, that he was going on the river "no matter what." So the morning of the send-off he was up and at 'em, showing he was ready. This show lasted a couple of days. We were doing about 25 miles each day. By the time he got ill again we were 50 miles downstream.

The doctor, David Gray, started him on fluids and medicine. He was not eating or drinking. By the end of the fourth day he was really sick so we pulled over on the north bank below some hills and a broad plain.

Three of us got ready to carry him ashore, and David Gray tried to rouse him by telling him to drink, and think of his wife. Shippee mumbled, "It's not worth it," then he slumped in our arms. We carried him to his tent. By midnight he was dead. Water in his lungs made it too hard for him breathe. The next morning we put his body into a yellow river bag. I had wondered if that meant we were going to carry him down river. But no, Gary and Toby were digging a grave. We had a ceremony for David.

We buried his body high enough on the plain that I think his grave was above flood level.

Later, I found the exact spot on a map, and it was just about 100 miles from Tuotuoheyen, as we had guessed at the time.

Why had David Shippee taken the chance on an unknown river? He was a young photographer, and National Geographic was interested in the expedition's story. This could have made his career. In the back of all our minds was the thought that successful completion of the exploration certainly couldn't hurt whatever else we wanted to do. On the expedition were a doctor, river guides, photographers, cinematographers, and news persons. All could use the publicity, if it was good.

An attempt was made during the night to set up the short wave radio to make contact with the road crew. We ran a wire between two oars, but by then the road team was 300 miles away with mountains between us. The wire was used because the radio's antenna had been forgotten. I don't know enough about SW radios to say if a wire was even a likely substitute. They were not likely to be listening for us anyway, as this section of the river had not been deemed dangerous, and we never got more than squawks and squeals. It was a more sober team the next morning as we thought about what had happened and what lay ahead. Before we left the United States, Ken asked us all if we could deal with the unknown. We all thought we could, but events proved differently. I remember telling myself to not even get a cut finger on this trip, staying healthy was that important. In Canton, I recalled, Ken told us there would be no helicopter rescues, we were really on our own.

This section of the river is called "The River of Golden Sands."

It was on a beautiful point of land where the Yangtze cuts through a mountain range, a place we called "The River at the Top of the World," for that is how it felt.

This was the river at the top of the world, still close to 14,000 feet, cutting across a plateau without trees, without permanent settlers, but not without beauty. This seemed to be the place where all the world's puffy white clouds were born, up in the dark blue sky. This was where you could see the sun rise almost below you on an incredibly distant horizon, where the darkness rolled away each dawn like a gray veil slipping down the western sky. This part of the river is called the Tongtian Ho, or "River to Heaven."

Just through the gap in the mountains we rounded a turn and espied this prayer flag array.

A cable cart astride the river.

Massive arms of the mountains sloped down from the heights along the river above Yushu. Similar to the Columbia River at The Dalles.

Eventually we saw villages on the slopes.

Drip-dry yaks leaving the river's edge.

The people were curious and friendly, running to view our seven rafts, bringing tea, carrying small children. They had seen other rafts when the all-Chinese team had floated by a month earlier. Whenever we pulled to shore for a lunch or photo break they gathered around, staring at us as we photographed them. Chu said many of them had not seen "round eyes" before.

Each stop we made was full of friendly greetings from people who maybe had never been more than 20 miles from their own villages.

It was amazing and at times I felt akin to Powell or other river explorers, greeting natives along the way. The river is not much used for commerce in this section.

We came across loggers, floating a log raft downstream from the mouth of a stream to the other side of the Yangtze where another stream entered. Note the bluer water entering from the left.

Ken Warren takes the tiny tot's hand.

Greetings were exchanged, and I have forgotten the phrases, but not the many faces.

We saw more people standing on the cliffs and running down to the riverbanks.

Behind them were small villages, with two and three story mud brick buildings.

Lunch breaks were near a couple of these towns, which were about 20 miles apart. Some of the villages had tall trees, perhaps poplars, standing as wind breaks, but for the most part there were no trees across the landscape. The whole team whooped it up when we did see a large tree close to the river.

At one stop we were given tea, loaded with yak milk.

At the Zhimenda Hydrologic Station on a tributary to the main river about 2 days above Yushu we were given fresh greens from the greenhouse garden.

About five men occupied the facility, and they had a green house to grow vegetables. They invited us into the living quarters to try making a phone call to the support team at Yushu, but the phone did not connect with Yushu. They gave us some dough buns, cooked, ready to eat. It was difficult to keep from scarfing them forthwith, as hungry as we were.

To supplement our diminishing food supplies we tied up upon seeing a sheep herder and his family.

Wife of the sheepherder

Supplies had not run out, but food was getting low. At one stop we bought a sheep from a nomadic herder, trading a knife and about $15 worth of Chinese Yuan. The herder and his son and wife were intrigued with our walkie-talkies and the Frisbee.

The sheep was butchered on the spot.

We ate sheep that night and for a couple more days.

About two kilometers above Yushu we saw a raft on the bank. Closer inspection revealed a sign, written by the support team telling us to let them know when we were arriving so they could roll the cameras. I got out and ran ahead, as our radios didn't reach anyone.

I had to inform Jan of Dave Shippee's death, I thought. But I didn't, letting Ken break it to her instead as he walked up the beach.

The joyous occasion of arrival was dampened considerably. Cameras rolling.

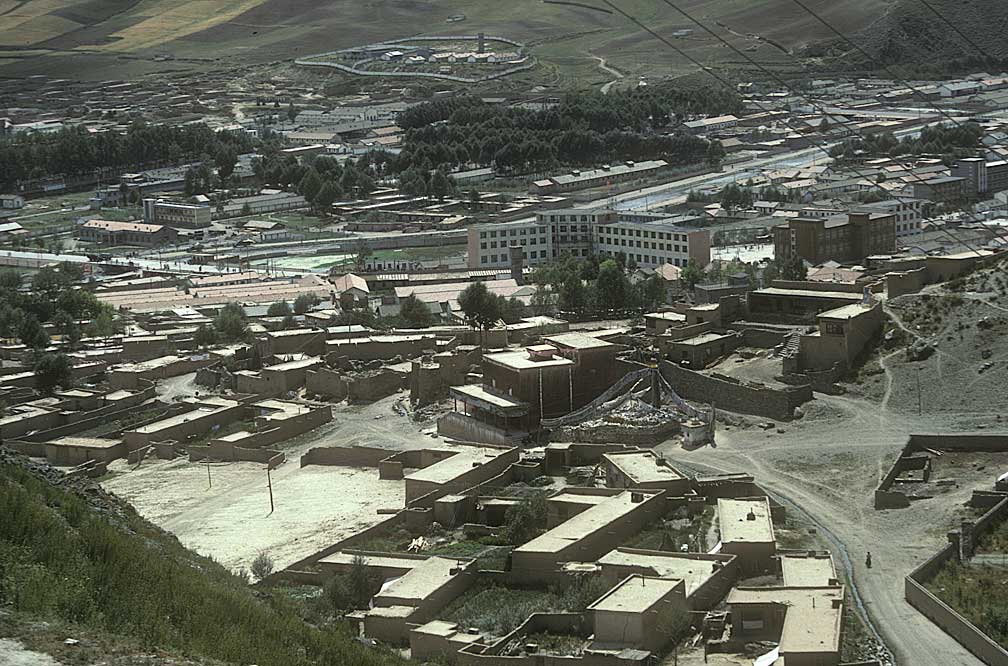

Old Yushu under restoration in preparation for tourists

Officials treated us to a tour of the city of Yushu, until then closed to foreign visitors. Much work was being done to restore the old city and the monastery.

Young man practicing a dance

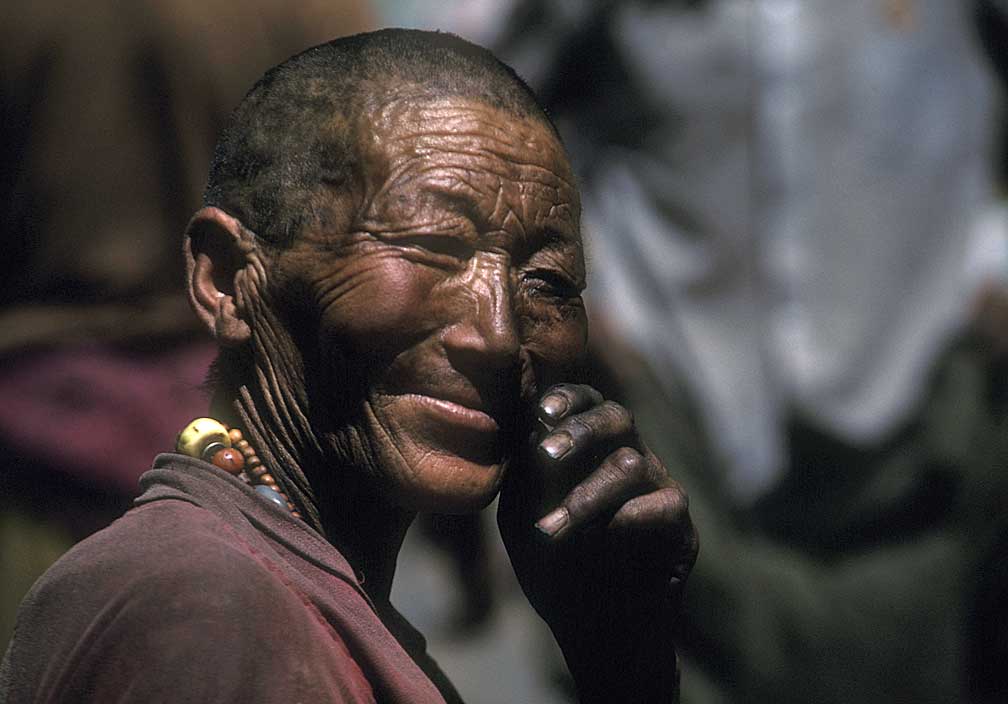

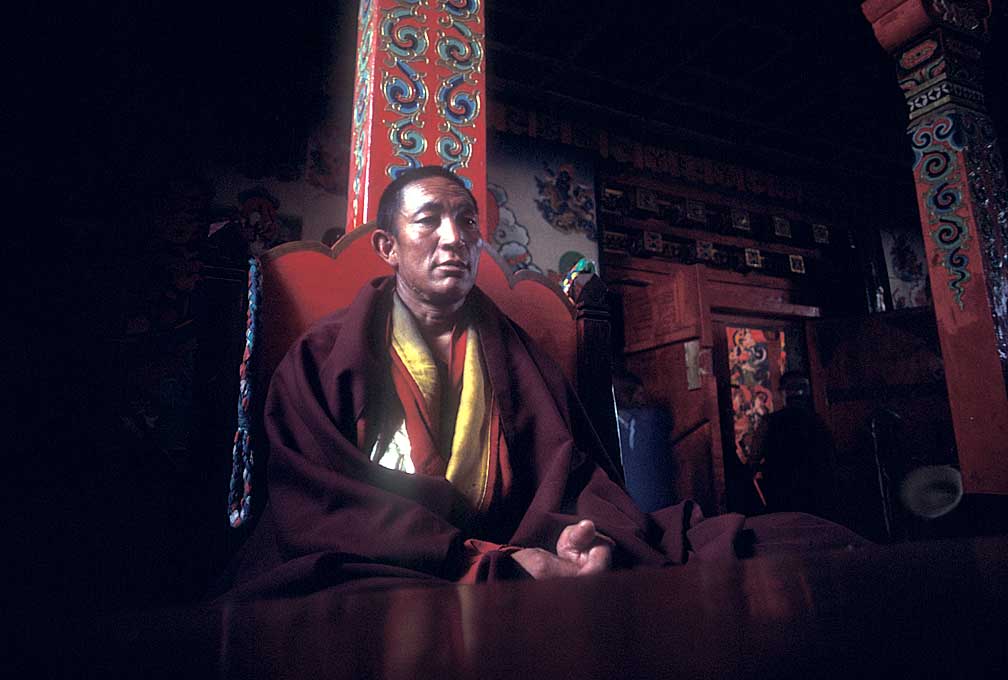

The monks were practicing a ceremony to welcome the Pachen Lama, the official Chinese version of Tibet's Lama, not the Dalai Lama.

In deep thought, a dog curls up in the corner. Not sure about the monk.

A monk with some status in Yushu

A monk with some hesitation, perhaps

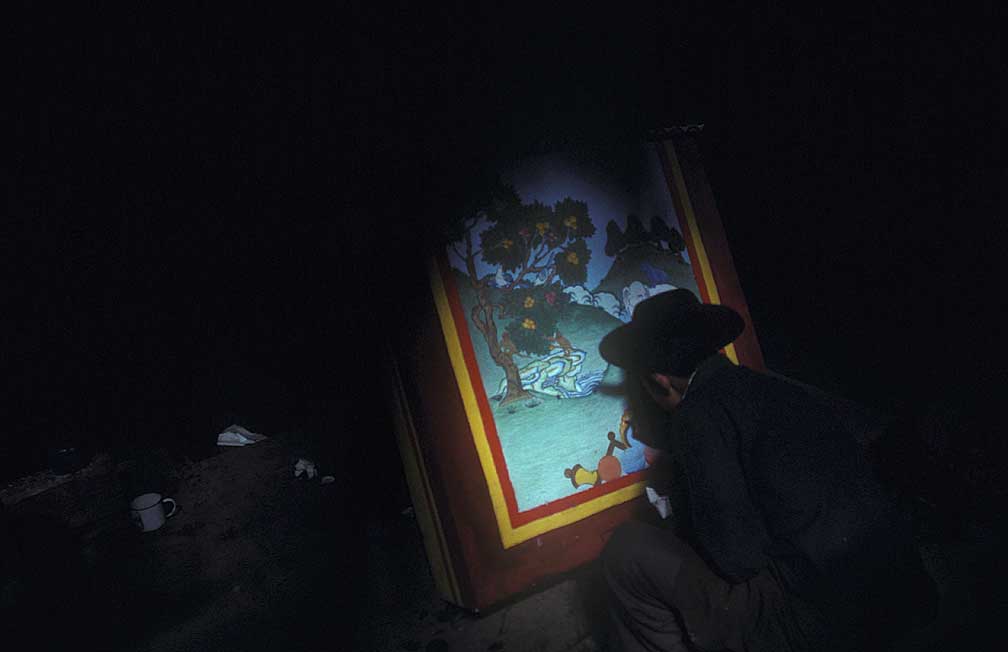

Artist at Yushu monestary

A traditional dance performance in Yushu

At night we attended a folk play performance and were invited up on the stage and given a round of applause by the audience.

Four members left the team at Yushu. This is how it happened. On our second morning the team voted to tell Ken they were having problems. I don't remember that vote as a mutiny vote. I was selected to ask Ken to a pow-wow so that the dissidents could ask him to turn over the leadership to Ron Mattson. They accused Ken of mismanagement and blamed him for Shippee's death, or at least for not calling in helicopters to rescue him. The matter was not up to a vote, Ken stated. This was his expedition and if anyone wanted to leave they could. He and the expedition were continuing down the river. There was some murmuring and the dissident ones decided to leave. I was glad for that, because as much as I trusted Ron, I knew that Ken was the only one who had a grasp of the whole picture.

PS: I (Paul Sharpe) don’t expect you to talk about my contributions to the trip or how it wouldn’t have proceeded from Yushu if I had not gone to Ken Warren immediately after the confrontation and told him that, regardless of whatever took place upriver with David Shippee, I was hired to do a job, that job was to film him on the river and if he was going down, so was I. He was pleased that someone was supporting him. When Dominy found out that I was going with Ken, he decided to come too as he was not going to let someone else make “his” film. (Dan admitted this to me years later). After that the Chinese guys decided to continue on. I’m not sure when you decided to come along. I remember the guys who were quitting confronting me angrily after I said I was going down river with Ken. I think they wanted the trip to end right there in Yushu if Ken wasn’t gong to step down as leader. :PS

Ken later he told me that he saw me standing there, waiting to see which way the wind was blowing, ready to go with whomever was staying on the river. I agreed; I wanted to go on with the adventure, no matter who was the leader. I did tell him, however, that I wished he treated everyone the way he treated me, with respect. He looked at me silently and nodded. The implications of that request were not lost on Ken. I think that Ken respected those who worked hard and he had a tough time with those on the team who held back from performing the everyday tasks: cleanup, latrine digging, dish washing, and so on. The next day we broke camp, with the four leaving on a bus for Chengdu, and Ken leading the rest of the team on to Dege.

This is the incident Outside magazine called a "mutiny." One could hardly call it a mutiny when four quit and the expedition continues. The captain retained command, he was not cut loose, set adrift on a bus to Chengdu. Captain Bligh and Fletcher Christian this was not. Nor was it the Caine Mutiny. No one accused Ken of being a coward. Just the opposite. The magazine never did publish a correct version of the events, preferring David McCrea's distorted view gleaned from interviews with the quitters, who had to make quitting look good by making the expedition leader look bad.

McCrea interviewed me but discounted what I had to say. I was dismayed when I read his account in the magazine; it was as though he was talking about a totally different trip. A year later, Shippee's kin brought a wrongful death suit against the Warrens and the film company. An Idaho court decided for the defendants, not believing the testimony of the quitters. Other accounts of our expedition miss no opportunity to take digs at Ken and report all the petty comments that detractors made. Sure, Ken kept his hair combed, but why not, he was being filmed. Sure, he wanted to be first, and he really thought that was going to be possible, despite the reports of teams ahead of us, including reports of deaths. Sure, we ran low on food and had to have peanut butter sandwiches for lunch, but that is all I usually have for lunch anyway, so it was not a hardship. We got hungry, but we did not starve, and besides, this was not a rafting trip on the Rogue, complete with guides, and I expected conditions to be even worse than they turned out. It demeans the authors of those accounts to repeat the behind the back comments that some team members made to each other, but not to Ken. But there is nothing that can detract from what we were about to do.

John Wilcox, adventure filmmaker, said, in a Paddling Magazine interview: "In my 30-plus years of expeditions I can’t recall

a single trip of that magnitude. I always said the Yangtze was an expedition

with a capital ‘E’. There were no fly-over capabilities and

there was no safety net." In May of 1987, Outside magazine

ran a story on the trip by Michael McRae called "Mutiny on the Yangtze,"

describing how four members of the team left the expedition, taking a

bus to Chengdu. But Wilcox disagrees with the assessment. "The whole

mutiny story was total bullshit," Wilcox says. "The only ‘mutiny’

was the doctor getting the hell out of Dodge."

Before we arrived in Yushu I rode in one raft, most of the time, rowing every other hour, just for relief. Without me catching on, the oarsman was training me to row because after Shippee died he had made up his mind to quit. When we left Yushu for Dege I had my own 18-foot raft to row. By following Ken and Ron in the whitewater sections, I was able to row some intimidating rapids. Even when I didn't do everything correctly I stayed in the raft and kept it right side up. My overconfidence leaped ahead; I thought I was ready for anything.

Our first big rapid below Yushu, photograph of Ancil Nance just emerging from inundation..

The first large rapid gave me a chance to get buried in water. We were able to pull over and scout the hole. Paul Sharpe paddling a kayak was out ahead radioing back that it was time to scout. From the cliff we looked down on 100 yards of standing waves that went right into a rock at a turn. The water piled up against the rock and the idea was to pull hard to the center of the river and stay off the rock. I rode through it first with Ken to get an idea of what could happen then he put me ashore and I went back for my raft. I wasn't able to stay off the rock and the water piled over me, filling the raft with another ton of water. A quarter-mile downstream I finally made it to quiet water and shore.

ON TO DEGE

The scenery was stunning, with the surrounding mountains coming to a steep stop at the river, which wound around great projections of land like a snake, making the distance between two points stretch from a quarter mile into 5 miles. Small villages interrupted greenish brown slopes and fields planted in what could have been oats. The fields looked like brown 32-hole golf courses. The homes were made of mud brick, rocks, and small timbers, with racks for hay drying on the roofs.

The whitewater sections were plentiful but not impassable, so I never had to get out my climbing gear and climb the canyon walls. Since I had signed on as a climber and dishwasher, the rowing was an unexpected gift. Before Yushu, when I had been a passenger in Bill Atwood's boat, I had felt it a great privilege when he allowed me to row his raft. Thanks to him quitting, along with Toby Sprinkle, David Grey, and Gary Peebles, I now had my own boat to row. Early on there was a pecking order. The oarsmen were like mini-captains, and the rest of us were passengers. There was some discussion as to who was really the best at picking a way through the obstacles. I followed Ken and Ron, and made it, so that was all I needed to know.

Since there were no rock walls to climb I helped the film crew tote tripods and gear to the cliff edges for shots that we were able to set up, looking down on rafts plunging through the cataracts. I missed rowing through two big ones because of that. The first one we called "Three Boat Rapid" and it may correspond to what the Chinese teams referred to as "The Gates of Hell." One report of this and the previous rapid place it upriver from Yushu, but that can't be, because here we are without the team members who left.

DEGE

Dege isn't on the Yangtze, it is up a small tributary a few miles, so when we pulled over under a bridge across the Yangtze we didn't see a city, just a few small buildings, and trucks ready to take us to town. The town sits astride the smaller river, with homes and sewers right on the river's edge. Ron and Paul had to try a kayak run in this new stream, and when they returned to our guesthouse they were more than glad to take a hot, soapy shower.

A tributary runs through Dege

Dege sawyers

Prayer papers drying at the printing shop

Dege is a bustling community, still high in the mountains, but with roads that usually remain open east to Chengdu and west to Lhasa. It was here that we heard we had not seen anything yet, as to whitewater. Ahead lay the real whitewater. Impassable. The Chinese team skipped this section. That did it! If they skipped it, we were going to run it! We rested, walked around Dege, and enjoyed the good food provided by our Chinese hosts, a welcome change from the canned and packaged dinners of the previous two weeks. We visited the Buddhist monastery, watched preparations being made for the arrival of the Pachen Lama, due to arrive in a few days. The guest house we were in was getting full, with guests arriving and expecting rooms previously booked, but taken by our team. We were able to rest a couple of days, however, and were anxious to get going again.

THREE BOAT RAPID

This one stopped us. It was too big for single rafts and we thought we had better portage. My raft was picked for the attempt at an overland haul. We spent hours getting the gear out and then dragging, tugging, lifting the 18-foot gray mass over the boulders. Strewn along the left shore, by an eddy below the stopper hole, were all manner of broken rafting and personal gear. It looked as though this was one place the all-Chinese team had capsized in their smaller rafts. There were caves among the rocks, which proved handy for our overnight stay.

The effort at portage was so difficult that Ken and Ron reevaluated the situation. Ron suggested lashing the remaining three rafts together, to form a craft three boats wide. This they did, and were able to run the maelstrom. Ron rowed the left side, Chu Siming, in the middle raft with a movie camera, and Ken was on the right oar as the three rafts slid toward the center slick. The drop was about 15 feet, a slanting tongue licking a giant boulder in the center where the rafts disappeared momentarily.

They emerged with a cascade of water pouring out of the boats and then crunched the left rock wall, where they were again inundated, scrunched onto another rock midstream, and then, clear going downstream. Ken radioed back that we should refit the portaged raft and catch up with the three-boat rig, which they would row to shore at a likely campsite. Easier said than done. River runners talk about "control." As in "So-and-so was out of control on that river." Let me get this one straight. There are times on all big white water where the boatman just sets up and lets the river take the raft through whatever is ahead. You don't stop in the middle of a big drop, you go where the river takes you. In that sense you are out of control. Much has been made of how we, in our multi-raft rigs, and we, in our closed bottom rafts, were not able to "control" the rafts. What a bunch of baloney! We always set up in the best part of the river and then rode the raft where the river wanted us to go. There was no other way. Sure, we could not stop, but if someone thinks that they could have done this river in a open bottomed raft with no weight value, they are crazy. Light-weight rafts would have been tossed like balsa wood models. The way we did it was the only safe way.

THE COLD WET NIGHT

The three rafts had gone ahead, carrying only three oarsmen. Left behind wereThe three rafts had gone ahead, carrying only three oarsmen. Left behind were two Chinese oarsmen, Zhang, and Xu; a Chinese news photographer and writer; the film crew and their gear, Paul Sharpe, the kayaking cinematographer, and myself. The idea was to load the remaining raft and float down to the camp that Ken, Ron, and Chu were establishing. It was late in the day, however, and our first attempts to drag the raft out of the eddy were not successful so we decided to wait until the morning of the next day, having exhausted ourselves.

That night we stayed in the caves among the boulders where we huddled for warmth, as most of our personal gear had floated on with the three rafts. It began to rain and the temperature dropped, but we were able to stay dry. The next morning we loaded the raft with a little of the gear and Zhang and I took the oars, with John Glascock along for ballast. We pulled on the oars, trying to get into the current, both in the upstream and the downstream end of the eddy, but we only got loads of water over the tubes, making it more difficult to get up speed to join the current. Then, as luck would have it we popped into the swift current, pivoted on a submerged boulder, and my oar snagged on my life jacket, dipped into the river at a steep angle, lifted me off my seat. John grabbed for me just as the raft was levered over. Upside down now, the raft was a roof, I remarked to John that at least the raft was emptied of water. We ducked underwater, and spotted Zhang floating downstream. The current was still swift, but there was no whitewater in sight, so we were able to get the spare oars off and use them to row, sort of, until we came to where the other boats had pulled over. We were able to control the capsized raft and did not need to right it. The three oarsmen on land were dismayed to see us, arriving upside down, knowing that the others were upstream without a paddle or raft.

Paul Shape filmed part of the capsizing, but a boulder blocked his view just as we flipped. So his film shows a raft, and then an upside down raft. Paul ferried film equipment from the eddy to camp several times; filling the small space his kayak afforded. Then it came time to tow and guide the others who jumped into the river with only their life jackets for aid. The river allowed them an uneventful float, and soon we were all drying off around a fire near an old stone hut, used by yak or sheepherders.

Cooking pots in stone shelter along the river

The raft flip had consequences we did not foresee. Our base radio was packed in a waterproof hard case. A thin rubber ring serves as a gasket and must be in place to keep the water out. The last person to pack the radio away neglected to put the gasket in place, and we did not know until too late that the radio no longer functioned. We did not have the correct antenna either.

Upon leaving Dege we were back in single raft mode, the river was hidden behind twists and turns; the cliffs sometimes obscured in mists. About ten miles from Dege, on the opposite side of the river we noticed a small house and tent. We pulled over. A man greeted us, and showed us around.

A woman was bent over some rocks, carving a phrase over and over on the stones. We were told it was "Om Mani Padme Hum." Roughly translated the prayer says, "The jewel is in the lotus." or "Good fortune to you."

High on the limestonecliffs above was a small structure where resided another monk in the mist.

Mani stones, carved with a prayer, lie about beneath the hills.

TO THE RIVER OF DOOM

The filming slowed the trip as it would take hours to set up, film, stop the rafts, pick up the land based crew, and get going again. But the expedition had to be filmed since Mutual of Omaha had paid big bucks to have it appear on ABC's Spirit of Adventure.

The first of the big efforts came when Paul radioed back that there was a large drop ahead and we should pull over to the left side of the river if possible. We did, just in time. The hole would have given single rafts a bad time so all four were diamond-rigged together making a craft 36 feet long and 24 feet wide, controlled by two men on each outside oar and two steering in the rear raft. That worked well, and they were able to guide the super-raft through the best part of the river. This was the second big rapid that I did not get to ride since I was carrying tripods and other gear for the film crew.

It took three hours to lash the rafts so we had a late supper that night camped on rocky ledges. The next morning I set off early with Dan Dominy, Kevin O'Brien and Paul Sharpe to set the cameras on a rock near the main hole. They each had a full sized 35mm camera. On the rafts were a couple of fixed movie cameras in waterproof housings, and the sound man, John Glascock had a handheld. He had also rigged microphones to record the passage. It was fun to watch and I wished I had been on board. The four-boat rig disappeared twice from view, so large were the holes, but it emerged downstream, oarsmen yelling victory. Paul left his camera with me and went back to kayak the whitewater while Dan filmed. Paul disappeared from sight a couple of times, but mostly bobbed along on top, making it look easy. "A piece of pie," remarked Xu.

Two hours later Dan, Kevin, and I caught up with the beached rafts. The day was getting long but it was felt that we could go a few more miles, or "K," as we had begun to measure it in kilometers. The river moved swiftly, and a bend blocked our view. Paul went ahead in his kayak. Within minutes he radioed for us to pull over because there was no way we could raft what he was seeing. The canyon here was high, steep, and twisting. We couldn't walk out. But Ken thought he spotted a way to make the run. The diamond rig was still intact so we went for it, all big-eyed and hearts pounding. This is where the story began, with Chu and Zhang being swept overboard.

Normal whitewater is rated on a scale of difficulty from I to VI, but this monster water was off the scale according to Ken and Ron. How far off we had no inkling, "Try XII," Ron suggested afterwards. For over an hour we crashed forward, being tossed first up, then down, then left and right. The noise of the crashing water and the groaning rafts made it hard to hear even a yell, like being in a train tunnel with the train bearing down. And on it went. We had rafts full of water, but finally, after the monster whitewater quit, we were able to pull ashore at a sandy beach with a cleft in the rocks that looked like it held a trail. We figured this was it, no more for the day.

We made camp, and assessed the damage to the rafts, two of which needed repairs, perhaps caused by oarlocks puncturing adjacent rafts.

The next day we went for another hour-long ride after filming what we called "Buddha's Hole." Named that by Paul as he told us to pull over or we would "see Buddha." Richard Bangs says this may be the same keeper hole the caused the death of three of the Chinese Team who were in the closed capsule.

Buddha's Hole. Paul Sharpe is standing on the left-hand rock median. He warned us to scout this one. We followed the V-slick, which punched us through just to the right of the hole occupying most of the river center.

PS: I (Paul Sharpe) am 100% certain that I never said that any rapid was unrunnable, either by radio or while scouting. I always felt there were safe ways to negotiate the dangerous spots, but that if you didn't scout the rapids ahead of time you could be in a deadly situation.

If I said "Oh My God" it was in response to looking into Buddha's hole while on the radio and what I knew would happen to you all if you didn't scout and just dropped in there. It was a hole that would most likely kill anyone who went into it. It was a hole so large that an 18 wheeler could drop in there and completely disappear. It was sucking water up from 100 feet downriver back into it. A raft could stay in there for days, getting endlessly hammered.

What I said was, “Oh my God, I’m looking at a huge hole. It’s going to be certain death if you drop in there. You guys will definitely need to scout this one.” When asked if there was a way around it I said “Yes, it looks like there my be room on the either side but you need to look at the line before you run it.” I never said that there was no way around it. I mean, you guys ran four rafts lashed together down the right side missing the hole. Obviously there was plenty of room there. :PS

We had been expecting the river to let up; thinking nothing could be bigger than what we ran the day before. Turns out we were wrong. From the shore we scouted this 75-foot wide, 30-foot deep "keeper hole" in the river which, if you hit it just wrong, would hold and re-circulate the raft. We filmed this run, and this time I got to ride, as the film crew didn't need any help. Chen Qun photographed the stills from the bank for China News Service. His photo shows our four-boat rig on the right edge of a massive hole, leaning toward, but not going into, the maw. It was over in seconds, and it was the deepest water hole I had been able to look into without entering.

Ron had repaired some punctures the rafts had suffered the previous day, so we came through Buddha's Hole just fine. The water was smooth for about a half mile. Paul was again scouting ahead in his kayak. All of our Motorola walkie-talkies were tuned for his warnings, which we had come to expect, and while not exaggerations, were warnings, which we had gotten used to. The worst of the water we ran anyway when not able to pull over.

We were not able to pull over this time. Too late to stop, river going too fast. The oarsmen pulled back toward the center. The left side of the four-boat rig plunged straight over a ten-foot-high rock, making a 12-foot long rip in the floor of the left raft; the one Ken and I rode. The other three rafts stayed in the main current, pulling the wounded raft with Ken and me at a twisted angle. I thought the rafts were going to tear their D-rings and snap the frames. The sounds of the twisting frames and rubber and the crashing water deafened us, again. I can still hear it in the back of my skull.

This water was bigger than the day before, and just as relentless. By now I have run out of superlatives. Monster, King Kong-sized water, no, Godzilla, waves bigger than a house. Somebody afterward said 30-foot waves. It was like being on the ocean. Halfway through, our raft disappeared. I reached for the adjoining raft and yelled at Ken, "What happened?"

"I don't know," he gurgled, as water by the ton crashed on us again.

We headed down a North Sea-sized trough with no raft beneath us, only hanging on to the ropes of the other rafts. The others were yelling for us to hang on, to get back in. Less then twenty feet away loomed a sheer rock wall, and the rafts were about to squash us against it. We lunged on with no time to spare. Bangs, in his book, Riding the Dragon's Back, comments that we were here "spinning out of control." Well, maybe. What I recall is that by pulling on the oars the men were able to keep us off the rocks and we went with the flow, not spinning at all. At one point I looked back and what I saw was not a waterfall, but a massive drop of smooth-faced water, too high to see over, perhaps 30 feet high. Ahead, it looked like we were going over another such drop. It was like going over a series of steps, not quite steep enough to be waterfalls. I flashed momentarily on Paul Sharpe, what could he have done, in a kayak, on the back of this gargantuan? No one could traverse this water and be "in control" no matter what they were in. As it turns out, Paul did it in his kayak by sneaking to the sides and avoiding the main thrash.

PS: The second time you mention when I urged the rafts to pull over to scout, I had not seen the rapid yet and as you guys had caught up to me before I was able to scout it. That's the rapid where the raft got pushed up onto the rock and dragged back off. There is no way I would have said it was unrunnable as I had not gotten a vantage point to look the rapid over. What I said was, “Theres a huge rapid ahead. You need to pull over to scout it, I haven’t seen it yet but I can tell it’s serious. The eddy is on the left, you guys need to pull hard to catch the eddy, now!” I never actually saw the rapid until after you guys had careened out of control through it.

I also know that, after an initial effort, Ken told the raft team to stop trying for the eddy at the top of the rapid. Two members of the river team confirmed this. That’s why the lead raft got pushed up onto the rock and dragged back off. You were out of the center of the current. I also know Ken blamed me in front of everyone before I showed up for the damage that had been caused to the rafts. But because he gave the command to stop trying for the eddy you guys neither caught the eddy nor were set up properly for the rapid.

When I got to the eddy where you guys were finally able to pull over, a half mile or so downriver, I saw one raft flipped upside down underneath the other three with a huge rip in it’s floor. I knew the force the river had exerted to make that happen and how lucky you all were to still be alive. That’s why I had an “oh my God” look on my face when I finally caught up to you guys and pulled into the eddy. It wasn’t because of my personal experience of running the rapid.

Ken had that attitude of putting his life into the watery hands of the river without being certain about how he was going to get down certain rapids. That’s why he didn’t mind giving the command to stop rowing for the scout eddy. Sort of a throw caution to the wind and hang on for dear life attitude. I saw that again the following year on the Chenab river in India. Not judging it. Just saying. :PS

AFTERMATH

What happened to the raft? It had folded under the other three because of the rip the length of the floor. It no longer had flotation. We rode this mutation the rest of the way over more monster water until we reached a flat section where we pulled over to check for other damage. We lost very little gear: a couple of tripods, a smashed hard case, a jacket and some food. My camera containers with exposed film were safe. We still had our base radio, or so we thought.

The most damage wasn't done to the rafts. Some of the team had had enough. The whitewater had been beyond expectation and belief. No one knew what lay ahead, and only a few were willing to find out. We had faced the unknown unwillingly in that last hour-long section, and survived. If we had scouted it would have been called unrunnable, and maybe we would have tried to hike out from the previous camp site, where we saw a trail, and where a Tibetan hunter had stood to see us off. As it was, we had run it, the river miles that the all-Chinese team said was not runnable. We had survived the River of Doom. It might be fun to go back some day and view this portion of the Yangtze from the vantage point from which the Chinese teams had declared this un-runnable, even in their enclosed rubber balls.

FIVE DAY CAMP

What lay ahead? This was on all our minds. The film crew decided they wanted to hike out. The Chinese team was in favor of rafting a few more miles and landing on the Chinese side of the river. We were camped in Tibet. Ken, Ron, and I were in favor of continuing on the river, thus we had an impasse. There was no way to tell the road support team, headed by Jan Warren, what our situation was. We found out later that since we were overdue they were worried also, preparing to send a search party. The Tibetan hunter, who had seen us at the campsite back in the "unrunnable" section after our first day of monster water, reported to Batang and the waiting support team that we were on the river below Baiyu. Jan began then to get horse teams to meet us.

For two days we discussed and cajoled. Paul decided he was going to paddle across to China and hike out. Ken didn't think that was a good idea, but couldn't stop him. He waved farewell, and we watched him leave his kayak on the rocky shore and he disappeared into the foliage, climbing. Days later, slogging through a snowdrift, a Tibetan villager found him and took him to his village and then to Batang, arriving before the rest of us.

PS: When we sat at that final camp where we were all together, Ken said one of the rafts was too damaged to continue and once again stated his belief that air support would be coming. I told him I was convinced there was not going to be air support. That I wasn’t going to sit there while we ran out of food. I told Ken I was going to paddle down the river and tell them we needed food and supplies. I initially planned to run the river by myself to get help. After scouting the first rapid below camp for an hour and studying the maps the Chinese guys had, I decided the best way I could help the expedition was to hike out. That way I could tell a rescue group exactly where you guys were. If I went down the river it would be more difficult for me to explain where you all were and how they might reach you. Plus, I was worried I might reach a point where it would be impossible to continue on and also to hike out. That’s why I made the decision to hike. I was having a great experience on the river. I think I was the only one. I sent the group back in to find you guys and they met up with you as you all hiked out.

While Ken loaded up his backpack for the his hike out with food, and didn’t tell anyone he was leaving except for Dominy, I only took two cans of tuna fish and some miso soup powder for what turned out to be a five day hike. Glasscock begged me to take him with me but I felt he would only slow me down.

After everyone showed up in Batang. I tried to talk Ken into continuing on down the river. He wouldn’t have any part of it. Dominy and the rest of you guys had left behind the exposed film and all the film gear. Since you continued a little ways down the river after I left, I didn’t know where that stuff was. I tried to talk one of you guys into going back with me to recover the film and gear. No one would come with me. I tried to get one of you guys to at least wait in Batang for me while I went back to try to recover the film but no one would. You all got out of China as fast as you could. I had to go by myself. Again, I don’t expect your version of the story to highlight any of what I did but you make me out to sound like I was afraid all the time and quit the trip. It was quite the opposite. In the end, I was the only one who wanted to keep going. :PS

Yes, the rest of us. We were still discussing. Ron Mattson, Chu Siming and I had explored downstream, and returned with a report that for at least 7 miles it was runnable, despite the large set of rapids just below our camp. The Chinese team perked up. With the film crew still adamant about no more river running, and while Ron and I were scouting down river a second day, Ken decided there was nothing for it but to hike up to the nearest village and get horses to carry out the equipment.

He didn't want to leave anything behind. He loaded his pack with more than any of us could have carried and began a trek back to Batang, a story only he can tell, which I have heard a couple of times. It was a long hike, which Dan Dominy filmed the beginning of. He met barking mastiffs intent on taking off a leg or two. A kindly woman showed him a place to rest, and finally he got a truck ride back down to the Yangtze and across the bridge to Batang.

MEANWHILE

While Ken was hiking up the trails, Ron and I came back with a more favorable scouting report, the river was good for at least 15 K. On the fifth day in camp, after the monster water days, we got the film crew persuaded to get back on the river. One raft was not repairable, so we set it loose as a test of the rapids. It did better than our subsequent manned efforts, not gaining even a pail of water.

We were back to three separate rafts, and still no one wanted to ride in my raft, being a newcomer to the sport. Ron and the Chu carried the film team, and so I was able to go ahead alone, experiencing the lead position for the first time. It was kind of a thrill, not knowing for sure, wondering about the next bend. Eventually all three boats got close and we noticed another obvious drop a quarter mile ahead. We pulled over to the Chinese side of the river. The next rapids were full of large rocks, keeper holes and just looked dangerous. So we made camp again.

The next day Ron and I did some more scouting and unlike the previous scouts, this one was along a well-worn trail. That changed the picture. All were agreed now to hike out, following the trail. After waiting one more day for me to recover from a bout of dysentery we took off on a trail system. It was well-worn in most sections. One steep climb was filled with switchbacks that were four to six feet deep ruts where centuries of travel could find no alternate route. Across the river we could see villages high on the hills, and below there were rapids, but we were at least 1000 feet away and it was hard to evaluate them. On the second day the trail led inland, away from the river. Just when we were trying to decide what to do, a Tibetan and his son arrived, hiking down the trail. With sign language and some help from a shared word or two, Chu was able to ascertain that we would not be able to hike to Batang.The man, named Bama, said we should follow him first to his village, 5 miles into the mountains, and from there we could travel to Batang on horse back.

ADVENTURE'S END

After two days of hiking with fewer calories than a Jenny Craig diet, we were now in heaven, or at least Shangri-La. The village had about 50 mud brick homes, two to four stories high, with only a door on the first level. Bama cleared a space in his main room, above the animal stable on the first floor. Here is where his family lived, but they made room for us. We were given cloth pads and animal skins to sleep on. We offered to buy a sheep for our meals, which Bama agreed to.

Looking back to the village as the mist closed in I was reminded of the scenes in Lost Horizon as they left Shangri-La.

Bama arranged for horses to be brought and on our third day in the village we set off, up the trail to the surrounding mountains, just as a rescue team arrived from Batang, with more horses. After a palaver we united teams and continued to Batang.

The trail away from the river gained height and worked to mountain passes.

It rained most of the time, and I did my best to take photos and keep my cameras dry. This was a brand new adventure, going overland from the Yangtze to Batang.

OVERLAND TO BATANG AND CHENGDU

The trail to Batang crossed two passes that seemed to be around 15,000'. Snow and sleet formed at the rocky, highest points, and then the rain continued as we dropped back to the jungle-like foliage of the lower hills. We rode small ponies, with packsaddles, for much of the trip, but at times the way was so steep we had to get off so the ponies could be sure of their footing. By the end of the first day we arrived at a large cave in the limestone cliffs next to what looked like the end of the trail at a huge cliff. It made me think of the "Hole in the Wall" gang and secret hideouts.

Our first night out we stayed in limestone caves.

Despite the rain, John Glascock was able to round up enough wood to make a fire whose flames leaped six feet into the air. We voted him the "Most Improved Camper." Food was chapati-like bread and yogurt, supplied by the rescue team. The second day began with a surprise. The trail continued up the cliff, accessed by a small crack that led to a steep valley, out of sight from the previous camp. This went up until we came to vast rolling hills covered with small plants and grass, which continued for several miles before dropping back down through a real forest, with many kinds of trees. Along the way we met a tradesman, bearing a great copper kettle, three feet in diameter, on his shoulders. His yaks were also loaded. We never did get his story, but, hunched over under his load, dressed only in loincloth and sandals, rain coming down, I'm sure he had one. By late afternoon we came to a road which led to a logging camp. A truck waited there to carry us about 20 K to Batang.

In the courtyard of the camp we posed for a team picture, minus Ken and Paul. What a bedraggled bunch. We arrived at Batang before supper, about twenty minutes after Ken Warren arrived on his truck ride from Tibet. Two routes, different stories, same ending.

Paul was there too, getting stronger by the day after having lost a few pounds on his trek. Ron had a package waiting for him, from his wife, Cheryl. He invited us to gather around as he tore off the brown wrapper. Inside were several layers of chocolate-chip cookies! We went nuts, eating almost all of them. Ron gave me a nudge and we left the cookie eaters. In the room we shared, Ron showed me what was under the cookies: about twenty Snickers and Milky Way bars! He shared these with me over the next few days as we waited for transportation to Chengdu and then Beijing. It was difficult to find good chocolate in China.

During the whole river trip Ron and I shared a tent together. We had similar levels of dirtiness and fastidiousness, so we made good tent mates. Imagine, living out of a tent for 53 days! Ron was a great oarsman and Mr. Fix-It. He had skills needed by any river expedition. Most important, however was his sharing.

Ron and I agreed that the trip was over. No fixing the rafts and getting back on the river. The rainy season was upon us as the expedition had taken longer than anticipated. When Ken asked us what we thought, we were ready with one answer: let's go home. Ken nodded his head, but I could tell he was disappointed. The permit to run the river would expire in a few days. We had accomplished much, but had not made it to the flat water at Yibin, where steamboats stop going upriver. We had covered 1,100 continuous miles from the source, however, and that was enough.

The Chinese government provided us with transportation to Chengdu and a plane ride to Beijing. On the roads to Chengdu from Batang we went through country I can only dream of seeing again: high mountain passes, small villages stuck against the sides of mountains with rivers crashing down next to them. Mountain climbers had been through here, particularly Kanding, a jump off point for climbs to China's highest mountains. The children knew about Polaroid cameras, and were disappointed that our 35mm cameras didn't provide instant prints.

A large boulder bounced across the road near Kanding. We slowed and there, just beyond, was a massive landslide, seconds old, covering the road. We waited a few hours while the road was cleared, using an old bulldozer with a track that kept falling off. Ron helped the mechanics fix it. I took more pictures.

The landslide blocked our way until a bulldozer was set to the task of clearing.

Futher on another smaller landslide had to be cleared. Reports of other slides came to us.

The road to Chengdu passed through small mountain villages. Here in Kanding we had a chance to get our teeth fixed.

Four women in Kanding

Chengdu, the western capital of China, is near a giant Buddha carved in stone on a tributary of the Yangtze, and near the Panda sanctuary, but we didn't visit these sites. We were worn out. As we waited to get a plane for Beijing all we could do was walk around the city and eat. There were great Chinese food restaurants everywhere. The same was true in Beijing. We did not visit the Imperial Palace or the Great Wall. We just wanted to get home. Funny how once that sets in nothing can be enticing.

When we got home we began to get an inkling of the misinformation that had spread about what happened on the expedition. Stories in The Oregonian, especially those by Rolla Crick, were excellent, given that no one had been able to talk to us, but rumors of our troubles were greatly exaggerated.

Note: This appeared in Paddler Magazine May/June 2001

First Descents: Expeditions for the Ages

10 Top Contemporary River Expeditions

Tom Bie

The Yangtze

Location: China Expedition Leader: Ken Warren Year: 1986

One of the most controversial expeditions of all time, the 1986 Sino-U.S. Upper Yangtze River Expedition ended short of its goal, but not before the group spent two months covering 1,200 of the most remote river miles on earth. Idaho photographer David Shippee died of altitude sickness during the ordeal and expedition leader Ken Warren and cinematographer John Wilcox were co-defendants in a court case surrounding Shippee’s death. Both were exonerated. Though Warren’s was only one of five major expeditions--including two competing Chinese teams--on the Yangtze in the mid 1980s (documented in Richard Bangs’ 1989 book, Riding the Dragon’s Back, The Race to Raft the Upper Yangtze), his is generally regarded as the truest attempt at a first descent.

"In my 30-plus years of expeditions I can’t recall a single trip of that magnitude," says Wilcox, now an adventure filmmaker in Aspen, Colorado. "I always said the Yangtze was an expedition with a capital ‘E’. There were no fly-over capabilities and there was no safety net." In May of 1987, Outside magazine ran a story on the trip by Michael McRae called "Mutiny on the Yangtze," describing how four members of the team left the expedition and hiked out. But Wilcox disagrees with the assessment. "The whole mutiny story was total bullshit," Wilcox says. "The only ‘mutiny’ was the doctor getting the hell out of Dodge."

Richard Bangs and the usual Sobek suspects, including John Yost, Jim Slade and Skip Horner, were on the Yangtze the following year. Though they portaged around the mighty drops of Tiger’s Leap Gorge, they did make it through the previously unexplored lower reaches of the Great Bend, below where the two Chinese expeditions had taken out the previous year.